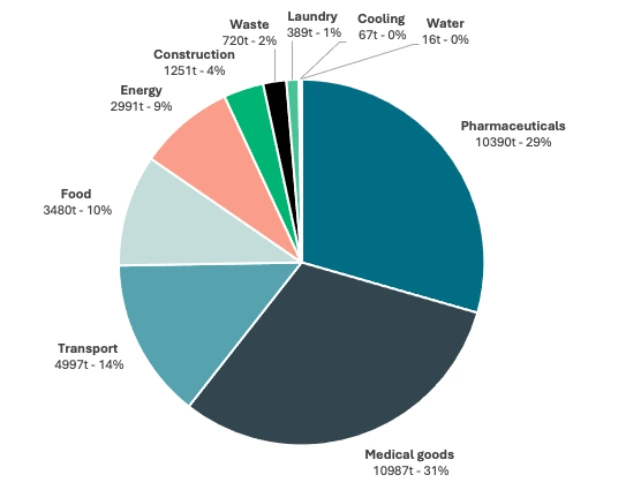

When we think of a hospital’s environmental footprint, we often picture smoking chimneys or idling ambulances. Yet, the data tells a different story: the most significant impact is hidden in the boxes and packages opened by healthcare staff every day. Globally, supply-chain emissions, also called Scope 3, account for 50–75% of healthcare’s total carbon footprint. Even excluding pharmaceuticals, the everyday essentials such as disposables, IT hardware, and medical equipment contribute over a third of an hospital’s total climate impact. In other words: the goods we rely on to heal patients are, ironically, contributing to the planetary health crisis.

Figure 1: Share of CO2-emissions per domain, in a 700-bed hospital in Belgium

Furthermore, the issue with these goods is not just about "going green". The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of our global supply chains, leaving frontline staff without essential PPE. By shifting toward sustainable procurement and strategic autonomy, hospitals aren't just cutting carbon emissions, they’re ensuring that the right tools are always available for the right patient, regardless of global geopolitical shifts.

At the same time, the regulatory horizon is evolving. While the immediate reporting mandates of the CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) may focus primarily on listed entities, the broader momentum of the European Green Deal remains undeniable. Whether through direct regulation or indirect market pressure, transparency is becoming the norm. This moves sustainability from a "nice-to-have" to a fundamental pillar of future-proof hospital management.

Shifting to circular economy

Today’s healthcare operates on a "linear" model: we extract resources, manufacture products, use them once, and discard them as waste. This "take-make-waste" approach is the primary driver of the sector's massive Scope 3 footprint. To achieve decarbonization, optimise resource-use and increase resilience, hospitals must transition to a circular economy, aiming to decouple high-quality patient care from constant resource consumption. This means treating medical goods as valuable assets to be kept in circulation, rather than disposable consumables.

Practically, this switch is guided by the R-strategies, a framework for circular economy, prioritizing prevention of waste over disposal. The journey begins with Refuse, Rethink and Reduce. The most effective way to move to a circular economy, is to challenge the necessity of an item before it is even purchased. This involves "stripping back" surgical kits to their essentials and questioning habits that lead to unnecessary waste. By Reducing the volume of items opened "just in case," hospitals achieve immediate "Lean and Green" wins.

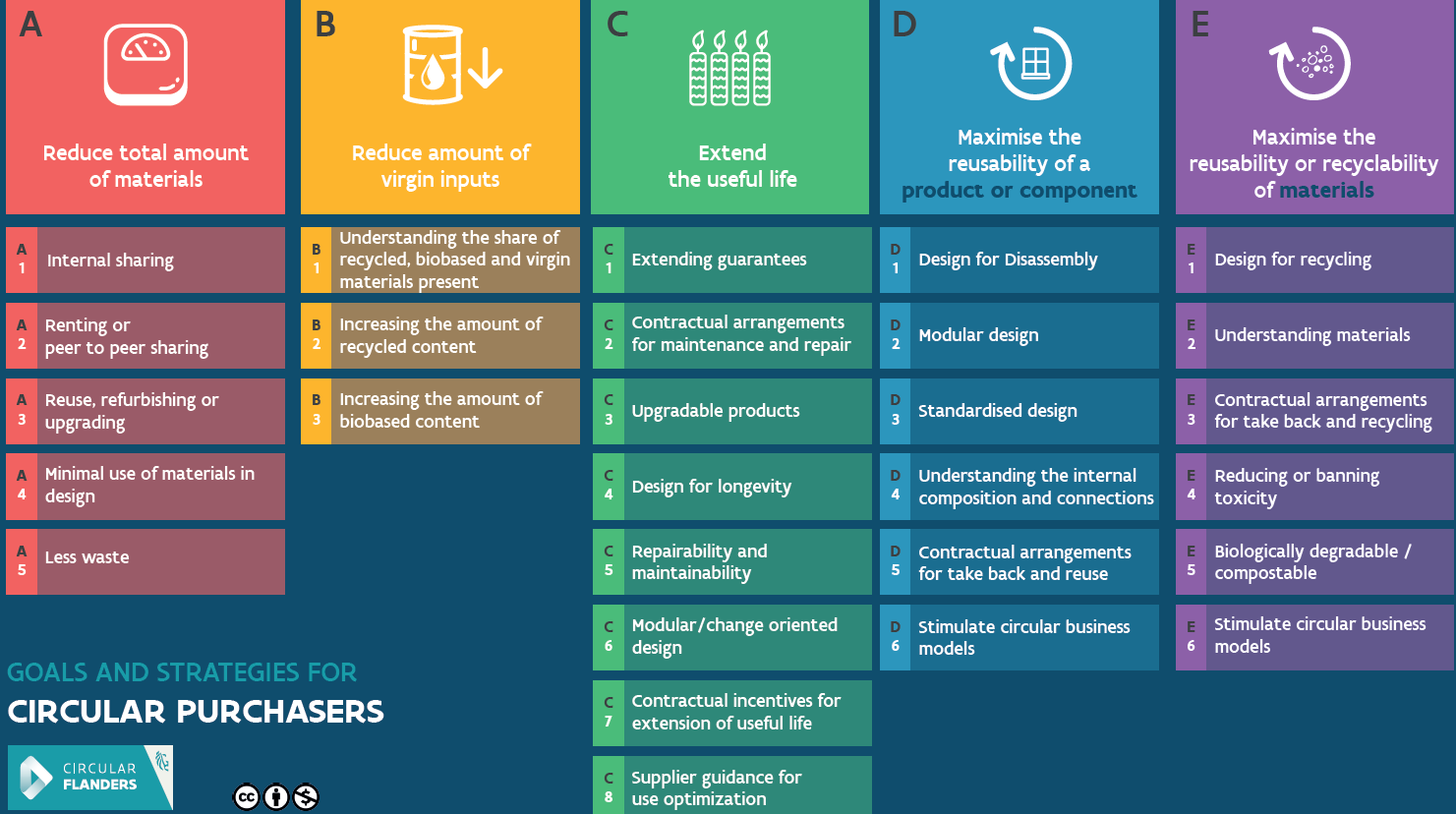

Figure 2: R-strategies (Circular Flanders, 2025)

When a product is clinically necessary, the focus shifts to high-value Reuse. This strategy replaces the "throwaway" culture with durable alternatives, such as textile drapes or stainless-steel instruments, designed to withstand hundreds of cycles of reuse. For complex technology where traditional reuse is not yet feasible, Remanufacturing (Refurbish/Repair) offers another path. Rather than following a cycle of premature replacement, we must treat high-value equipment, from patient monitors to diagnostic imaging systems, as enduring assets that can be upgraded and restored to peak performance. This strategic life-extension ensures that the embedded carbon and critical raw materials remain within the healthcare system, avoiding the heavy environmental and financial toll of unnecessary decommissioning and incineration.

Further along the spectrum sit Recycle and Recover. While recycling is often the first thing people think of when discussing "going green"; it is a very ineffective circular strategy. Recycling is energy-intensive and often results in "downcycling," where high-quality medical grade polymers are turned into lower-grade products like park benches or shipping pallets, eventually leaving the loop anyway. Furthermore, contaminated clinical waste often cannot be recycled at all, leaving energy Recovery (incineration) as the final, least desirable option. While recovering energy from waste is better than landfilling, it still represents a loss of the raw materials and the high carbon investment that went into manufacturing.

By understanding that recycling is a "failure of circularity" rather than the goal, hospitals can refocus their efforts where they matter most: at the earliest stage, where waste is prevented before it is even created. By systematically applying these R-strategies, procurement teams move away from end-of-pipe solutions toward a model that preserves value and builds a truly resilient, low-carbon supply chain. This holistic approach ensures high-quality care is delivered sustainably without exhausting natural and social capital.

Three areas of intervention

1. Systems

Procurement

Figure 3: Goals and strategies for circular purchasers (Circular Flanders, 2025)

This alignment ensures that sustainability expectations are credible and attainable. While requesting formal Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) demonstrates high ambition, positioning them as an aspirational benchmark or phased expectation (rather than a strict barrier) prevents the exclusion of smaller, innovative players. By asking targeted questions about durability and repairability, hospitals can still act as "launching customers", shifting the wider market toward long-term sustainability and resilience.

Procurement criteria only work if staff have the right skills. Many buyers excel at price negotiation but lack training in sustainability metrics or Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). Initiatives like the NHS’s Green Champions Hub and the EU’s Public Procurement of Innovation program show how carbon literacy and structured training enable greener purchasing decisions.

"Circular procurement acts as a driver for innovation, a lever for reputation, and an anchor for resilience: essential today, defining tomorrow."

Logistics

Transitioning from a "buy-use-discard" model to a circular one requires a fundamental shift in hospital logistics. On the incoming side, hospitals must rethink inventory management; reusables often require more storage for circulating stock compared to the "just-in-time" delivery of disposables. However, the most significant change lies in organizing Reverse Logistics. In a linear system, logistics ends at the ward's trash bin. In a circular system, "return loops" are essential, moving used goods back from the ward to a central point for reprocessing.

Implementing this requires a designed-in recovery system: clearer bedside sorting, dedicated transport loops, and a logistics team that treats "used" goods as valuable assets rather than waste. By closing these internal loops, feeding items back to the Central Sterile Services Department (CSSD) or external partners, hospitals reduce reliance on volatile global markets. This transforms a waste stream into a reliable, internal supply of tools, strengthening both environmental and operational resilience.

2. Medical goods

Medical goods are the most visible intersection of sustainability and patient care. By rethinking procurement and usage, hospitals can achieve major environmental and financial gains without compromising safety nor quality.

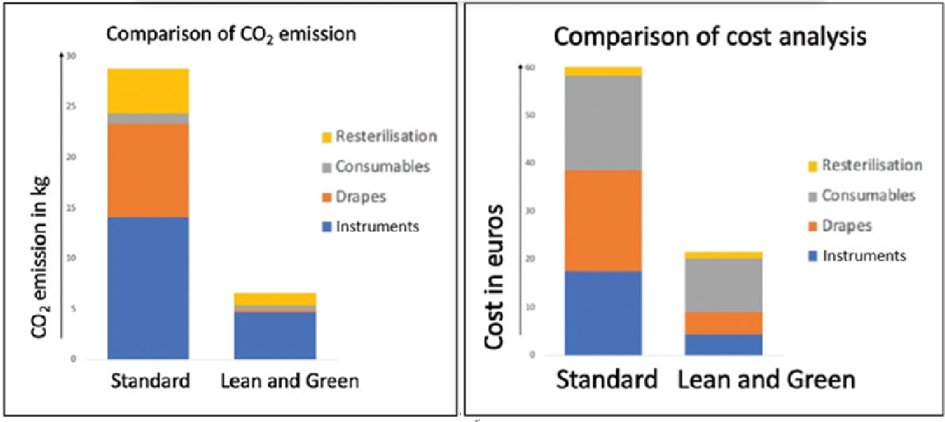

Surgical sets offer immense potential. A UK study on carpal tunnel release (Kodumuri, 2023) compared conventional methods with a streamlined "lean and green" approach. The standard operation produced 28.8 kg CO₂e, while the lean method, using essential instruments and fewer disposables; reduced the footprint by 80% (to 6.6 kg), cut waste by 65%, and lowered costs by 66%. Crucially, it saved 20 minutes per procedure, enabling two extra operations per day. Similar results are seen in cataract surgery, hernia repairs and dermatology, where lean kits deliver the same outcomes with less waste and emissions.

Figure 3: Comparison of CO2 emissions and procedural costs between standard and "lean and green" carpal release method (Kodumuri, 2023)

Furthermore, high-value technical equipment deserves scrutiny. For complex technology, refurbishment and professional repair offer a vital path. Under strict frameworks like EU MDR Article 17, devices can be professionally restored to peak performance, ensuring embedded carbon and raw materials are preserved within the healthcare system rather than lost to incineration, if Member States allow it and conditions are met. LCAs confirm that remanufacturing substantially lowers emissions while maintaining safety.

Hospitals must address the pervasive "just-in-case" culture that leads to significant clinical waste. A study on hand surgery revealed that an average of 11 items are wasted per case, totaling over totaling 441 kg CO₂e and over $2,000 in costs across 85 cases. Surgeons estimate that 26% of opened sterile single-use items go unused, yet most are eager to reduce this inefficiency. In the US alone, hospitals waste $15 million annually in unopened OR supplies that could be safely redirected. Adopting lean sets, stocking only essentials, and empowering staff through education are the next critical steps in eliminating this spillage.

3. Non-medical goods

While medical products often draw the most focus, non-medical goods contribute significantly to a hospital’s footprint. Digital transformation offers immediate gains; for instance, the NHS App’s wayfinding feature allows patients to manage referrals digitally, cutting emissions by 97.8% per letter and avoiding 30 million printed sheets, saving 6,600 tonnes of CO₂e. Transitioning to QR codes and digital forms ensures both staff and patients access real-time information without the waste of physical brochures.

Cleaning practices offer further opportunities for impact. UV-C disinfection reduces reliance on chemical cleaners, while probiotic cleaning shows potential to lower both costs and hospital-acquired infection rates. Food and beverage services are another high-impact area. By sourcing local produce, implementing plant-forward menus, and re-serving unopened, portion-controlled meals, hospitals can reduce waste while directly improving patient nutrition.

Lastly, ICT devices and e-waste require urgent attention. The WHO reports that electronic waste is the world’s fastest-growing waste stream, yet only 22% is recycled globally. By extending device lifespans and collaborating with certified recyclers, an approach supported by the EU Circular Electronics Initiative, hospitals can recoup value from hardware while significantly reducing environmental harm.

Driving change

Lasting sustainability in healthcare hinges on the people and processes inside the hospital walls. For many healthcare staff, "Net Zero" can feel like a distant administrative goal, but in practice, every decision on the ground matters. Clinical staff are the "eyes on the ground." International experience shows that when staff are empowered, small, bottom-up innovations drive systemic impact:

- Surgeons identify instruments in standard sets that are opened but never used.

- Nurses adjust how many packs are opened during procedures and ensure correct bedside waste sorting.

- Pharmacists pinpoint where overprescribing leads to avoidable waste and expiry risks.

- Logistics assistants can prevent overstocking through “first-in, first-out” inventory management.

- Administrative staff can reduce paper by moving to digital patient information or by using email and patient portals instead of printed letters.

Procurement cannot be left to administrators alone. When procurement officers and clinical teams collaborate, they align contracts with actual clinical needs rather than theoretical estimates. Hospitals that close the gap between the office and the ward will make the fastest progress.

While staff insights spark the transition, true circularity is impossible without a robust Central Sterile Services Department (CSSD). Every reusable surgical instrument, gown, and container must pass through high-standard sterilization before it can safely return to the ward. A well-organized CSSD makes reuse both reliable and traceable, transforming small, bottom-up innovations into scalable, hospital-wide practices.

By enabling safe and efficient reprocessing, the CSSD acts as the engine of decarbonization, cutting emissions and lowering costs without compromising clinical safety. To realize this potential, hospitals must treat the CSSD as a strategic asset rather than a back-office utility. This means investing in capacity, leveraging automation and robotics, and including CSSD expertise in all procurement planning from the very beginning. In a sustainable hospital, the CSSD is the infrastructure that makes green efforts possible.

A resilient future

By greening procurement and entering a circular economic model, hospitals ensure that they can provide safe, affordable care within planetary boundaries, independent of fragile global supply chains. By aligning systems, goods, and people, hospitals protect both their patients and their resources. However, moving from a shared vision to tangible results requires a shift in daily operations. To bridge the gap between high-level sustainability goals and the reality of the ward, leadership must focus on three decisive areas:

- Move beyond upfront purchase prices. Evaluate goods based on their full lifecycle, accounting for waste disposal costs and supply chain reliability.

- Administrative logic must meet bedside reality. By empowering Green Teams and tapping into clinical expertise, leadership can identify "lean and green" opportunities to eliminate waste before it ever reaches the hospital floor.

- Strengthening sterilization capacity and automation is the most effective way to scale reusables and break the cycle of high-carbon, single-use dependency.

At NZHI, we help hospitals make medical goods more sustainable without compromising safety or quality. From reducing the footprint of surgical kits and PPE to integrating reuse through your CSSD, we support hospitals at every stage of the transition. With science-based tools and hands-on expertise, we ensure that your efforts deliver real impact. Let us help you move from intent to impact.

We thank Alexandra Vandevyvere (Circular Flanders) for her expert review and valuable contribution to this article.

References

- Building Better Care, 2022, NHS App reduces carbon emissions

- International Hospital Federation, 2024, Sustainable procurement in hospitals

- Kodumuri et al., 2023, Reducing the carbon footprint in carpal tunnel surgery inside the operating room with a lean and green model: a comperative study

- Mölnlycke Health Care, 2024, Sustainable procurement in the health care sector

- Circular Flanders, 2025, Circulair aankopen, Focus op waardebehoud

- UNDP, 2020, Sustainable Health Procurement Guidance Note